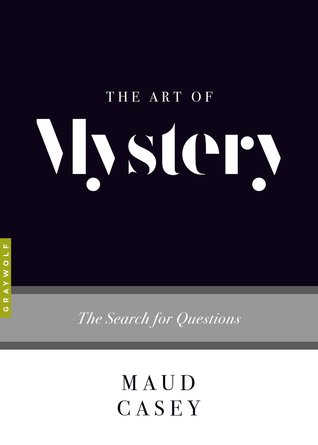

This is the fourteenth book in Graywolf’s “Art of” series. Some I’ve found useful (like Joan Silber’s The Art of Time in Fiction and Charles Baxter’s The Art of Subtext) and others aroused my curiosity but not a compulsion to read straight through.*

These are collections of essays on themes; some are short and dreamy whereas others are carefully arranged like term papers. They are the type of writing book which might be best approached as a casual coffee date, so that you pull the book off the shelf when you have time to sit and sip and think and you can select the right piece for that moment in time.

Read straight through, like a text, some pieces are bound to feel more satisfying than others, in the way that many readers rush through collections of short stories and say they are uneven, because each piece requires and rewards a different kind of attention.

The opening piece in Maud Casey’s collection is “The Land of Un”, a short and tight meditation on mystery. Perfect introduction. And it contains tidy little snippets like this: “If mystery, the genre, is about finding the answers, then mystery, that elusive yet essential element of fiction, is about finding the questions.”

The next piece, “Unknowing, or the Construction of Innocence”, is three times as long and begins with 1873 and moves into a detailed consideration of Isaac Babel’s “Awakening” and Dezsö Kosztolányi’s novel Skylark, in which “the extraordinary relies on the ordinary for its existence”.

An unexpected layer to these slim volumes is the sense that one has, after finishing the final essay, of whether or not one would have much to discuss with this writer. About the writing and about the work – and often the answer to that is not very mysterious because Graywolf chooses smart people, musers and meanderers, with whom you would enjoy sharing a decanter of wine – but also about everything else, the wider goings-on of the world.

Which of Vivian Maier’s images most intrigue her and which authors’ characters’ secret lives keep her up at night: these are the bits which offer insight as to whether I would like to seek out Maud Casey’s fiction, too. But it was her admiration of and fondness for the work of Barbara Comyns that sealed the deal for me. Yes, indeed. More Maud Casey for me, please.

Great stuff for writers.

*I’ve already discussed here one of my favourites in the series.

Maud Casey’s The Art of Mystery: The Search for Questions. Minneapolis: Graywolf, 2018.