I discovered Dorothy Allison’s fiction through browsing in a women’s bookstore in London, Ontario: my introduction was her book of essays Two or Three Things I Know For Sure (1995).

Reading “Place” reminded me that I should return to that collection and to Skin: Talking about Sex, Class and Literature (1994), which I picked up shortly afterwards.

Allison’s style is straightforward and passionate and, for me, it has the perfect mix of subjective experience and instruction; she tells me enough about herself that I feel I have a context for what she’s saying, and she leaves enough space for me to move into the text alongside her, with all the bulk and heft of my own experiences.

She begins this piece by mentioning that there are certain places we North American readers all recognize as being easy to capture on the printed page: the American South (with porches, pick-up trucks and Southern grandmothers), Boston (city of blizzards), Chicago (the Projects), and boroughs of New York City (with Jews eating pickles and having their own grandmothers). Of course her tongue is wedged solidly in her cheek because she is pointing out the exceptions to these “rules”, even as she is saying that “Their place is a given”. (6)

And immediately I think of writers like Linda Hogan and Rebecca Wells, novels like Zadie Smith’s On Beauty, Sara Paretsky’s Warshawski mysteries, and Mark Helprin’s Winter’s Tale and Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence: stories rooted in the South, Boston, Chicago and NYC. And, indeed, some grandmothers come to mind!

But before I can settle into that, Allison is speaking about how she could not find the places she knew in the pages of American fiction, that she had to create the world of truck stops and grocery stores and diners, to invent it on the page. “Place is often something you don’t see because you’re so familiar with it that you devalue it or dismiss it or ignore it. But in fact it is the information your reader most wants to know.” (7)

There are a lot of great observations in this essay (and I’ll mention another one of them in a minute) but what I loved most was her admission that she used to sneak into other people’s dorm rooms, not to pilfer, but to see what they had (and didn’t have). I’ve never done anything like that (but only because I never stayed in residence in school, not out of moral compunction) but I know that, at open houses, I spend far more time inspecting the current residents’ belongings than I spend examining floorplans and room dimensions (and that it’s more fun than it “should” be).

I appreciate that kind of honesty. Even though I understand that it might make for squirmy moments had I been her dorm mate.

It’s not as though what Allison is saying here is breaking news. We all know that place is important. But Allison’s essay is a worthwhile variation on that theme. “What I have is the landscape in which I grew up and the landscapes that I have adapted from every damned book I’ve ever read, and every damned book I’ve ever read is in the back of my head while I’m reading yours. Every place every other writer has taken me is in me. Can you take me somewhere no one else has?”

Good stuff for writers.

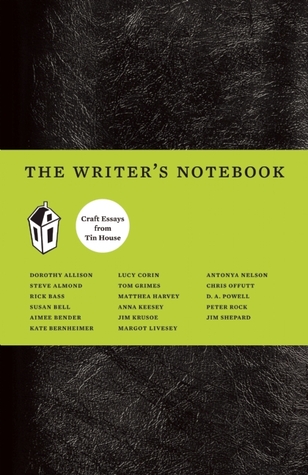

Tin House The Writer’s Notebook: Craft Essays from Tin House (Tin House Books, 2009)