Most of my reading about writing this year has been about concrete aspects of the craft, how to summarize your work for the pitching process, for instance, or how to prepare a book proposal.

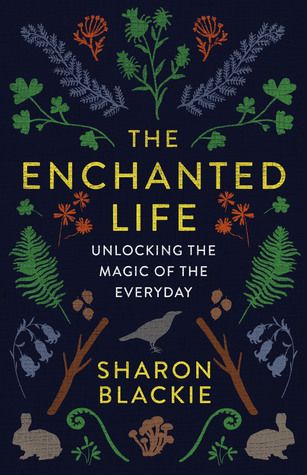

Sharon Blackie’s book is not a to-do primer but a to-be primer. It’s about foundational rather than executional work.

Which makes it sound a little intimidating, doesn’t it? And that’s appropriate. Because despite the blooms and bunnies on the cover, this is a heavy read.

Heavy partly because of the style (the author is a “reformed academic”) but heavy mostly because it requires a lot of readers.

Sharon Blackie observes that we tend to focus on horizontality, on our positon on the ground, but she reminds us that we can change our two-dimensional way of looking at the world into a recognition of its depth and complexity.

One of the ways in which she became aware of her personal embeddedness in the world was to more fully inhabit the space in which she now lives (on the Isle of Lewis, in the northern Hebrides, off the coast of Scotland).

She came to realise that she inhabits a biosphere within a biosphere, that she is living in a ‘weatherscape’, not simply a landscape. Reading about her experience in this new space is interesting on its own terms.

“The wind and rain that I was railing against are the forces which had shaped its physical attributes over the millennia, and determined the nature of the land which I loved so fiercely – the water-logged moors and bogs, the hundreds of tiny lochs scattered like fragments of broken mirror across the peatlands to the north, the vastness of a vista that stretched for miles, and across which your gaze could travel uninterrupted by trees or shrubs.”

Blackie, however, presents her personal experience as a doorway through which readers can step to more fully and completely inhabit our own familiar spaces.

One important habit to readopt/nurture is the habit of play. (It’s easy to see how this connects with creativity to bolster a writer’s work on multiple levels.)

“Above all, no matter how foreign it has become to you, and no matter how challenging an idea it might be, learn to play again. We find so many things to occupy our days that have purpose, but unstructured play has no purpose other than pleasure. Practise it with a child, a dog, a cat, your lover, a friend. Or practice it alone: just learn to mess about, to fiddle with things, to splash in puddles, make sandcastles or snowmen, paddle in the shallows, like a child.”

She also encourages the art of attention. (Observation certainly strengthens creative work, adding to credibility and fostering fresh possibilities.) A set of exercises follows each chapter, encouraging reflection and sometimes requiring concrete work. This is not the kind of book which instructs you to go to the store and purchase a journal, but it is the kind of book that makes you think so much that you will want to write.

“Wonder is different from awe, which is usually defined as the sense of having an encounter with some presence larger than ourselves, something more powerful, and a little bit frightening. In a state of awe, we feel humbled. In a state of wonder, we feel possible.”

There – in that state of possibility – that’s where the value of this work for a writer lies.

Sharon Blackie’s book is what I wished to find in Women Who Run with the Wolves; it is a book I will return to at intervals, perhaps even more often than those craft-oriented volumes.

Great stuff for contemplative writers.

Blackie, Sharon. The Enchanted Life: Unlocking the Magic of the Everyday (Ambrosia, 2018)