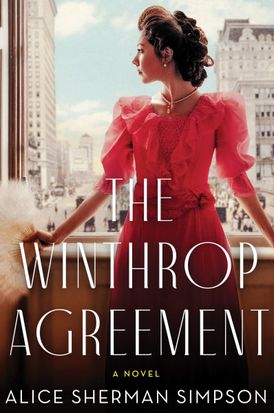

The cover of Alice Sherman Simpson’s The Winthrop Agreement conjures up a certain kind of reader and, frankly, it’s not my kind. At least that’s what I first thought.

Picture this: a young woman in profile in front of a window, looking away from the reader and indirectly at the slightly unfocused, sepia-toned skyscrapers of historic New York City behind her, her brilliant coral lace-and-taffeta dress and rosy skin a startling contrast until it fades into darkness that affords the perfect backdrop to a sophisticated font.

It’s been invited to the same party as the book covers of Paula McLain and Tatiana de Rosnay, and the blurb describes it as “[p]art history, part romance, with a twist of gothic” and refers to “Bridgerton”.

But I read Simpson’s Ballroom, her 2014 debut novel, rooted in linked narratives that, cumulatively and deftly, prompt profound questions about relationships. About how we connect and disconnect from others around us. And how we pursue and create the futures we imagine for ourselves—sometimes tragically.

The Winthrop Agreement ranges from 1893 to 1928 and, stylistically, it straddles a dedication to historical accuracy, but recognises that modern readers often prefer an anachronistic approach to storytelling. Don’t let the facts stand in the way of falling fast into a story.

You can practically see the folders stuffed with Simpson’s notes—world events and characters’ experiences for each year in charts and timelines—and the stacks of reference books lurking on flat surfaces in her study. There’s no doubt she’s done her research, both deliberately and accidentally (by consuming other people’s historical fiction and older novels).

It’s also unsurprising that Simpson is a visual artist with a particular interest in dance. Her scenes are so acutely imagined, that there were moments where I felt like I was reading the prop department’s notes for a limited series on TV or a classic Merchant-and-Ivory-styled film.

At first this slowed my roll, especially as the headings for each year seemed to accentuate how deliberately time was passing at certain junctures in the characters’ lives. (This way of marking time reminds me of Amor Towles’ A Gentleman in Moscow, another historical novel segmented into years, where some years are encapsulated on a single page and others require dozens for their account—because, as in real life, some years are pivotal and others routine.)

It’s true that Ballroom was more tightly constructed—orchestrated, even—right from the start, but the opening chapters of The Winthrop Agreement evoke one of my favourite novels about a young woman born to an immigrant family in New York City, who must find her way in a world which offers every opportunity and no opportunity: Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

When Mimi became my Francie, I was hooked. And Miriam’s view of the city from the rooftop is akin to Francie’s fire-escape view:

“…she felt like she could see the whole world from he sixth floor. She could see both down-and uptown: the buildings, the river, the ever-changing cloudscape in the sky, and the waves of laundry on lines stretching from building to building, dancing in winter, motionless in summer.”

Simpson’s attention-to-detail captures more than it seems. Sometimes it’s all about the visual but sometimes the novel’s themes are encapsulated there. As with this garment: “She wore a swan-bill corset, all the rage in Paris, to create an S-curve torso shape despite how uncomfortable it made her.” Readers can imagine the garment’s appearance, but its symbolic importance reminds us of the confinement and challenges faced by women of that era.

The wealthiest women’s corset strings are pulled the tightest, and this novel is all about class. Beginning with a young woman’s arrival at Ellis Island. Mimi is not a Winthrop, and most of what she knows about the wealthy comes from novels she’s read. This is how she understands privilege, by first observing it on the page and then, much later, observing it in the world around her:

“Young wives held their husbands’ arms while pushing babies in proper prams. It was the world she knew about from Edith Wharton’s books—one of quiet refinement. Not illustrated figures from Vogue or words in a library book that fed her imagination but one in which she could turn round and round and see in its entirety.”

This is where the novel’s conflict is rooted, too: in privilege. Particularly in how it’s levied by men against women, by the wealthy against the working-class. “The Winthrops are very smart people,” Mimi is advised: “They are part of Society—the Four Hundred.” (There are, however, characters who challenge the status quo: as Mimi’s experience expands, she finds supporters who have and lack access to wealth.)

One of the most satisfying elements of Simpson’s novel is how naturally she reminds us of her story’s context in bookish terms with artsy specifics. As when we see Mimi borrow a Kate Greenaway book from the public library to read to her neighbour, the premiere performance of Dvořák’s New World Symphony at Carnegie Hall, or tickets tucked inside a copy of Willa Cather’s Oh, Pioneers!

So even if I’d rather have seen a young girl with her library books on a Brooklyn fire escape on the cover, The Winthrop Agreement is a really good read: don’t let the taffeta and tulle put you off!

Published by HarperCollins and HarperPerennial US and HarperCollins Canada