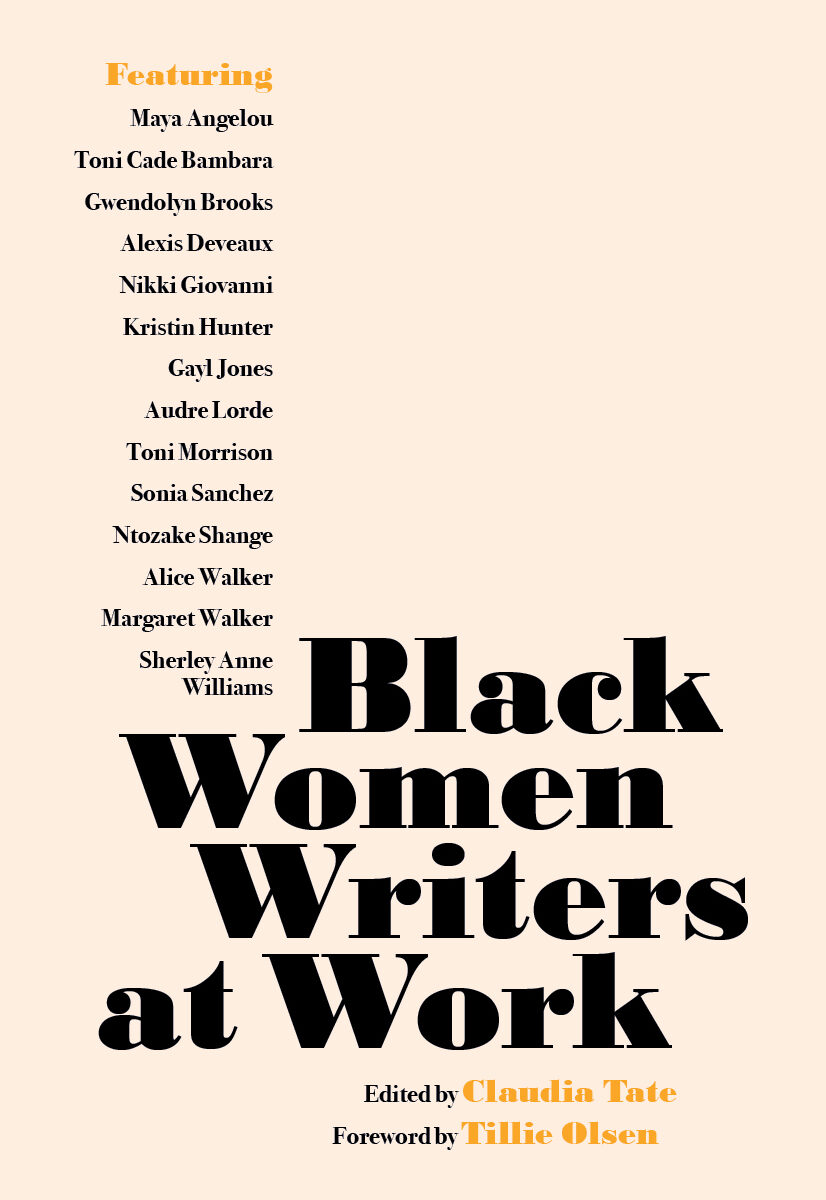

The inimitable Tillie Olsen contributes the foreword to Black Women Writers at Work, which she describes as “one of those rare, rich source books for writers, readers, teachers, students—all who care about literature and the creation of it.”

In her introduction, Claudia Tate outlines her intention of balancing the personal and literary content of the interviews. Not too personal—“disrobing exposés”—but not so literary that “the writers’ experiences and interests are divorced from their works.”

The artist’s life and art are “inextricably interlinked” she observes: both important in “an environment of diverse, and often conflicting, social traditions.” In fact, nowhere more so than in America, she says. There, the “social terrain” is increasingly “complex, controversial, and contradictory” where “a racial minority and the ‘wearker’ gender intersect”.

It’s this quality, the precise blend that Tate curates, which makes these interviews so satisfying to read. We have the biographical details that Toni Cade Bambara shares: “My mama had been in Harlem during the renaissance. She used to hang out at the Dark Tower, at the Renny, go to hear Countee Bullen, see Langston Hughes over near Mt. Morris Park.”

Alongside her talk of process: “I begin on long, yellow paper with a juicy ballpoint if it’s one of those 6/8 bop pieces. For slow, steady, watch-the-voice-kid, don’t-let-the-mask-slip-type pieces, I prefer short, fat-lined white paper and an ink pen. I usually work it over and beat it up and sling it around the room a lot before I get to the typing stage.”

And reflections on underlying philosophy and motivation. Which is often powerfully intertwined with contextual details. “People have to have permission to write, and they have to be given space to breathe and stumble. They have to be given time to develop and to reveal what they can do. I’m still waiting for another Gayl Jones novel or two so I can gauge whether I’ve been reading the first two correctly.”

Claudia Tate conducts her interview with Gayl Jones after Jones had not only published that third novel Bambara was waiting for, but had published a collection of stories too. (Tate invested energy, focus and time into her interviewing.) She opens with questions about an interview another writer conducted with Jones a few years prior, to discuss whether she views her writing as orchestrated or spontaneous. Thus not only are these women writers who are engaged with one another’s works, but there’s a broader cultural discussion about the works’ value and resonance unfolding in the interviews also.

Tate’s specific questions about Jones’ 1975 debut, Corregidora, get granular: talk of perspectives and influences, for example. But there are big questions circling around identity and the role of storytelling too. After referencing Jones’ second novel, for instance, Tate asks how Jones’ ideas about storytelling impact “her listener, the evolving story, and especially your narrator”.

“I think of myself primarily as a storyteller,” Jones replies, “not only the author as storyteller but also the characters. There’s also a sense of the hearer as well as the teller in terms of my organizing and selecting events and situations.” She talks about interior monologues “where the storyteller becomes her own hearer” and how “consciousness or self-consciousness actually determines her stories’ events, illustrating her point with by returning to specifics in her work. These conversations strike a balance between natural and purposeful.

Some of these interviews are only a dozen pages long, but they feel dense with both information and personality. Some are more than twice that long and, yet, each exchange offers something new to the conversation.

I first read these interviews a few years after the collection was published, because I was obsessed with Audre Lorde. Of the other writers, I had read Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, some of Nikki Giovanni’s poems, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. Returning to it, I have read nearly all of these writers and multiple works; I come up short with two poets (Sonia Sanchez and Sherley Anne Williams) and novelist Kristin Hunter (with a copy of Margaret Walker’s Jubilee on my shelves, but unread).

It’s truly a delight to reread these exchanges in view of another sort of intersection: their having first been published in 1985 and, again, nearly forty years later.

A great resource for writers.

Claudia Tate, Ed. Black Women Writers at Work. 1985. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2023.