Rick Rubin being a music producer—he co-founded the hip-hop label Def Jam (think Run-DMC and LL Cool J) but was also behind albums from artists as varied as Lady Gaga, Metallica, Weezer and Johnny Cash—didn’t put me off.

I’ve written about Questlove’s Creative Quest (2018) and Rakim’s Sweat the Technique (2019) here: both worthwhile resources for writers, written by musicians (with Ben Greenman and Bakari Kitwana, respectively).

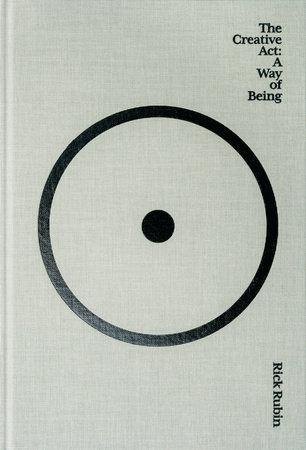

The Creative Act is written with Neil Strauss and the presentation is striking; it suits an artist whose trademark is a bare-bones sound.

That’s what caught my eye initially: the packaging (the production). But this passage on the first page secured my interest: “Creativity doesn’t exclusively relate to making art. We all engage in this act on a daily basis.”

There are a lot of core ideas in this volume that resonate with me. The book is organised into “78 Areas of Thought”. It begins with “Everyone is a Creator” and ends with “What We Tell Ourselves” and, in between, are countless relevant topics—from Greatness to Adaptation.

I’ve already recommended The Creative Act to someone who loves a pick-up and put-down and pick-up-again sort of read. Because Rubin’s Areas of Thought are not linked. You could read for a few moments, perhaps with a cup of coffee or a glass of lemonade, before resuming your work. The clarity and precision is striking (and seems to reflect Rubin’s philosophy…that bare-bones approach).

These days, I’m on a Mary Oliver Notice-Everything kick, so these three bits stood out for me.

From “Practice”:

“Awareness needs constant refreshing. If it becomes a habit, even a good habit, it will need to be reinvented again and again.

Until one day, you notice that you are always in the practice of awareness, at all times, in all places, living your life in a state of constant openness to receiving.”

From “Nothing Is Static”:

“The world is constantly changing, so no matter how often we practice paying attention, there will always be something new to notice. It’s up to us to find it.

And, from “Inspiration”:

“Train yourself to see the awe behind the obvious. Look at the world form this vantage point as often as possible. Submerge yourself.”

The prose feels like it has emerged from an editing exercise: is it possible to make this sentence more concise? This paragraph? This segment? How much can we cut while leaving the Essence intact? (“Essence” appears between “Non-Competition” and “Apocrypha”.)

Between the Areas of Thought, there are some epigrams. Right before “Inspiration” we have this: “Talent is the ability to let ideas manifest themselves through you.” If reading a few pages is too much for your schedule, how about a few lines. How about two. I’m all for this: I regularly trick myself into stretching by telling myself that I only need to get on my mat for one minute. Sometimes we really do need just a few words of encouragement to refocus on work we are resisting.

Rubin also offers some slightly more interactive elements. There’s a bolded list of Thoughts and Habits Not Conducive to the Work which begins with “Believing you’re not good enough.” There’s a section at the back with 14 pages of lines seemingly intended for readers to fill with their own words. And there’s an Area of Thought titled “Breaking the Sameness” based on exercises he has artists do in the recording studio (like altering volume levels or isolating particular sounds or focusing on only a single line).

That’s what I wish Rick Rubin had focussed on more: Breaking the Sameness.

There are no new ideas in any of the books I’ve written about here, but all those other writers have contributed something of themselves to their work on creativity. Questlove writes about chefs. Rakim includes such diverse memories and anecdotes that he covers the ground between Mickey Mouse and MLK.

But my broader concern is that things feel same-y because Rubin relies on the work of other creatives and doesn’t credit them. Those fourteen pages at the end could have been citations, references or, at least, recommendations—but that’s not Rubin’s priority.

This struck home (the sports metaphor will make sense soon) with this, in the Habit section: “The way we do anything is the way we do everything.” In the context of creativity, he’s highlighting consistency in this chapter.

That first sentence is a familiar mantra in my everyday life, and I was surprised to learn years ago that its genesis is the sports world. (Vince Lombardi is a popular theory for its origination.)

Though I haven’t researched the statement’s origins myself, I know enough to recognise that Rubin is quoting someone else. Without acknowledging their contribution to his thought process, to his published work.

I don’t credit Lombardi every time I utter this phrase, but I make it clear it wasn’t my original thought. Some sports guy made it a Thing. If I was going to cite it in my own work, however, I would have an obligation to get to the bottom of this. After all, Rubin says that an “artist earns the title simply through self-expression” and not by repeating other people’s ideas.

Maybe this isn’t the only instance of a lack of attribution in The Creative Act. Maybe it’s the only one I…noticed.

A questionable source for creatives.

Rick Rubin with Neil Strauss. The Creative Act. New York: Penguin Press, 2023.

I’m afraid this sounds a bit like the Reader’s Digest ‘How to be a Writer’ – all worthy stuff boiled down to short attention span pars. I like long form arguments – essays and books. And I must say I prefer ‘How I write’ or ‘How she wrote’ to ‘How you can be a writer too’.

That said, I think it is important to be aware that we are all creative in big and small ways, especially if we think about what we do.

It does feel rather like that, but now it’s hard for me to be objective about it; it left such a bad taste in my mouth, the realisation that he wasn’t attributing any of the other creatives and thinkers whose ideas are presented as his, and his alone, here. Anyway, maybe he’s not actually writing for creative people, maybe he only wants to raise his own profile as a creative…. /sigh