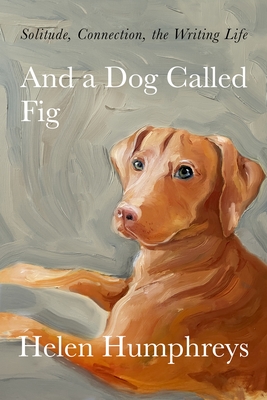

This is a most suitable companion for last autumn’s resource, Miss Chloe, in which A. J. Verdelle considered her relationship with Toni Morrison in the context of Verdelle’s life of letters, as reader and writer. Here, Helen Humphreys considers her life as reader and writer in the context of the relationships she’s had over the years with her dogs—most recently, Fig.

It’s hard to imagine this book without the dogs, and even though I’ve never had a years-long dog friend, I flagged several passages about them. “If all else fails in a conversation,” Humphreys notes, “particularly when writers are forced to socialize with one another at a literary event, I know that if the person I am speaking with has a dog, we will never run out of things to say.”

When she talks about Fig’s fidgeting while trying to prep her for a walk, she discovers an unexpectedly simple solution:

“I can’t believe I didn’t think of this before and have been fighting her this whole time when instead I could have just let her hold something in her mouth and made the whole enterprise much easier. Another example of the way a dog tells us what to do with them, and if we’re paying attention and not fixated on having our way, by listening to what they’re trying to communicate, we could get along with them better.”

Organically, from this realisation, this emerges: “This is not dissimilar to writing, where it is more effective to listen to intuition instead of trying to force your will upon a piece of work.”

She seamlessly stitches the two topics together, structurally and granularly: her relationships with dogs and her relationships with creative projects. And just as each dog she has loved is unique in her experience, so each book has been: “Each new novel requires that everything be learned all over again, because no two books are alike, and there are different sets of problems requiring different solutions when creating each one.”

Humphreys also contemplates the relationship between reading and writing: “It was reading that made me want to be a writer. I had cried uncontrollably for an entire day after reading Charlotte’s Web and was so affected by stories—unable to separate them from real life—that I decided the only way to loosen their hold on me would be to create them myself, because then I would know what was coming in the story and wouldn’t get so upset.” As a young reader and burgeoning writer, she could have selected several stories to illustrate her point, but E.B. White’s novel is perfect in the context of her relationships with four-legged and wild creatures.

For those familiar with Humphreys’ work beyond this book, there’s an additional layer of interest as she discloses elements of process for specific projects. About Leaving Earth, for instance, she writes: “I couldn’t figure out how to transition from one scene to the next, so I simply ended a scene and moved on to another one. This made the pace fairly quick, which, luckily for me, suited the story I was telling, so the short scenes don’t betray my lack of ability, and instead seem to be there as a deliberate device.”

And readers familiar with her body of work will not be surprised to find grief a central tenet here: “The natural world became even more important to me than it had before, and the smallest wonder in it was enough to calm my spirit for another day.” Her prose is spare, which affords the opportunity to deep emotion to settle between the sentences and paragraphs: readers coping with a recent or long-ago loss may find additional comfort here, perhaps unexpected in a volume which also contains valuable writing advice.

And A Dog Called Fig is a meditative and tender book about loneliness and companionship, love and grief, based in reflections on a life shared with dogs and shared with story; Helen Humphreys illuminates that the way we build (and lose) relationships is not all that different from how we create (and release) narratives into the world.

An excellent resource for writers.

Helen Humphreys. And a Dog Called Fig: Solitude, Connection, and the Writing Life. Toronto: HarperCollins, 2022

I’ve never had nor wanted a dog, but partners have made me understand the strength of feelings between dog and owner. So I understand why Humphreys might want to use caring for a dog as a metaphor for tending to her work.

What highlights for me though, why she is a writer and I am not, is her reaction to Charlotte’s Web. I am a voracious reader and a fluent writer but ‘writers’ are writers because every experience compels them to write, and I have never felt that.

The neighbour’s dog people-sits us when her family is out-of-town, so I’ve gotten to know a dog rather well after all, but Humphreys manages to capture the relationship so astutely that I don’t think one needs to have had personal experiences with dogs to get where she’s coming from.

Even though other writers might connect with Humphreys’ feelings about the need/desire to shape the world with words, whether as a protective measure or for some other reason, I wouldn’t take it that you’re not a writer because that’s not true for you.