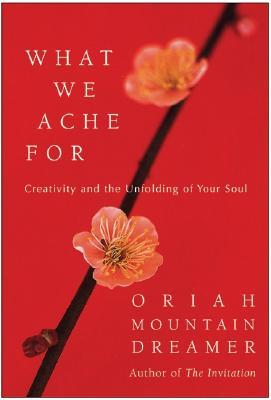

Simply by reading the title and author’s name, you will have an inkling of whether or not there’s a match to be made between you and this book. There’s the prominence of the word ‘soul’ for one thing, and the fact that the author adopted this name based on a message she received in a dream for another. And if you are the kind of person for whom an inkling matters, you are in good company and, if you count Natalie Goldberg among your favourite authors of books about writing and you have completed (or dreamed of completing) Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, you will feel like you’ve found your circle.

The emphasis on spirituality and personal growth did not suit my current frame of mind (and, further, I was craving a book on creativity in general, not about writing specifically) but I was encouraged to read on by this passage: “We have to let go of our ideas about ideal conditions for beginning if we are going to start.” With my work routine disrupted by a recent move—and compounded by a protracted illness—I struggled to focus; this simple concept (familiar, but freshly present, and in print) snapped my resolve into place.

What kept me reading was the author’s reference to one of my favourite writers (“reading the book The Stone Angel by author Margaret Laurence…made me want to write”) and to a writer whose work I have admired in general, whose work felt particularly pertinent with Russia’s war on Ukraine, the ongoing war in Ethiopia, unrest in Lebanon and continued conflict in Syria:

“Susan Griffin’s books Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her and A Chorus of Stones: The Private Life of War are two that repeatedly reinspire me to remember the mysterious process whereby writing or any other creative endeavor, can reveal the wholeness of life and the meaning embedded in interwoven colors and sounds and stories.”

I was reassured to discover this truism on these pages: “Sometimes it just takes a shift in perspective to help us see the world a little differently, to spark the imagination in new ways.” And I, too, took comfort in the works of others, while I felt unable to do my own work: “Getting in the mood to do our own creative work may mean deliberately cultivating our connection to a particular expression of someone else’s work.” At times, I marvelled at the room in these new surroundings (both indoors and outdoors) and thought that this might be true for some—“Too often we have little sense of spaciousness in our lives”—but, for me, broader spaces felt disorienting and strange.

At the end of each chapter, there are things to think about, sometimes things to write about. Mostly, the text seems to speak directly to a single reader, but occasionally it’s clear that the audience is a group or class, working through the book methodically and collegially.

In the “Doing the Work” chapter, readers are invited to complete the following phrases:

“I am committed to…

I find it difficult to persevere at…

I am patient with…

I am impatient with….” Although likely most useful for those who write primarily for personal growth, What We Ache For contains some solid advice.

Fair stuff for writers, good stuff for journallers.

Oriah Mountain Dreamer. What We Ache For: Creativity and the Unfolding of Your Soul. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005.