Whenever I look at the list of books about writing that I’ve considered on this site, I feel a pang of disloyalty.

Most of the books that had a fundamental impact on the way that I think about writing are books that I read a long time ago, books whose titles are not listed here, books whose ideas have no gratitude expressed towards them here.

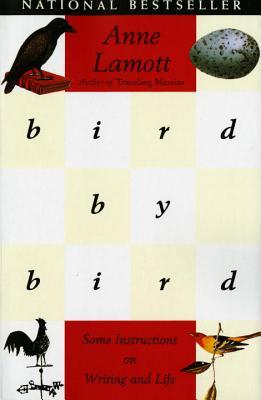

When I decided to re-read Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird this year, that’s what I was thinking about. It was a deliberately planned pilgrimage. But I was nervous about it.

Sometime between 1994 and February 2012, I did pick up Bird by Bird again, and I hadn’t loved it with the same fervour that I had when I first discovered it. After only a few chapters, I set it aside and wondered if I hadn’t grown out of it.

After that, I stopped recommending it as widely as I had, even though it was one of the books whose names still came immediately to mind when I considered influential books on writing. After that, I looked at my copy warily, like you look at a favourite food that’s been tainted by the memory of having eaten it on an evening that transformed into a particularly painful morning-after.

But now I can comfortably refer to it as a favourite once more. If I ever find the notes that I made from that first reading (if, in fact, I made notes, because all I remember is racing through it, even taking it into the tub, so attached was I), I might find that I noted completely different passages, but the number of flags that marked the remarkable passages of this re-read was an impressive tally indeed.

What makes Bird by Bird such a vital resource for me?

First, the specific.

“One line of dialogue that rings true reveals character in a way that pages of description can’t.”

“If there is one door in the castle you have been told not to go through, you must. Otherwise, you’ll just be rearranging furniture in rooms you’ve already been in.”

Next, the general.

“Writing is about hypnotizing yourself into believing in yourself, getting some work done, then unhypnotizing yourself and going over the material coldly.”

“Perfectionism is a mean, frozen form of idealism, while messes are the artists’ true friend. What people (inadvertently, I’m sure) forgot to mention when we were children was that we need to make messes in order to find out who we are and why we are here – and, by extension, what we’re supposed to be writing.”

Also, her bookishness.

“I read more than other kids; I luxuriated in books. Books were my refuge. I sat in corners with my little finger hooked over my bottom lip, reading, in a trance, lost in the places and times to which books took me.”

“Becoming a writer can also profoundly change your life as a reader. One reads with a deeper appreciation and concentration, knowing now how hard writing is, especially how hard it is to make it look effortless. You begin to read with a writer’s eyes. You focus in a new way.”

And, finally, her voice.

“There are moments when I am writing when I think that if other people knew how I felt right now, they’d burn me at the stake for feeling so good, so full, so much intense pleasure. I pay through the nose for these moments, of course, with / lots of torture and self-loathing and tedium, but when I am done for the day, I have something to show for it.”

“To be engrossed by something outside ourselves is a powerful antidote for the rational mind, the mind that so frequently has its head up is own ass – seeing things in such a narrow and darkly narcissistic way that it presents a colo-rectal theology, offering hope to no one.”

It’s Still Great Stuff for Writers.

Anne Lamott’s Bird

by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life (1994)

Pantheon Books, 1995